When Did Cars Start Using Catalytic Converters? A Complete History & Impact

When Did Cars Start Using Catalytic Converters? A Complete History & Impact

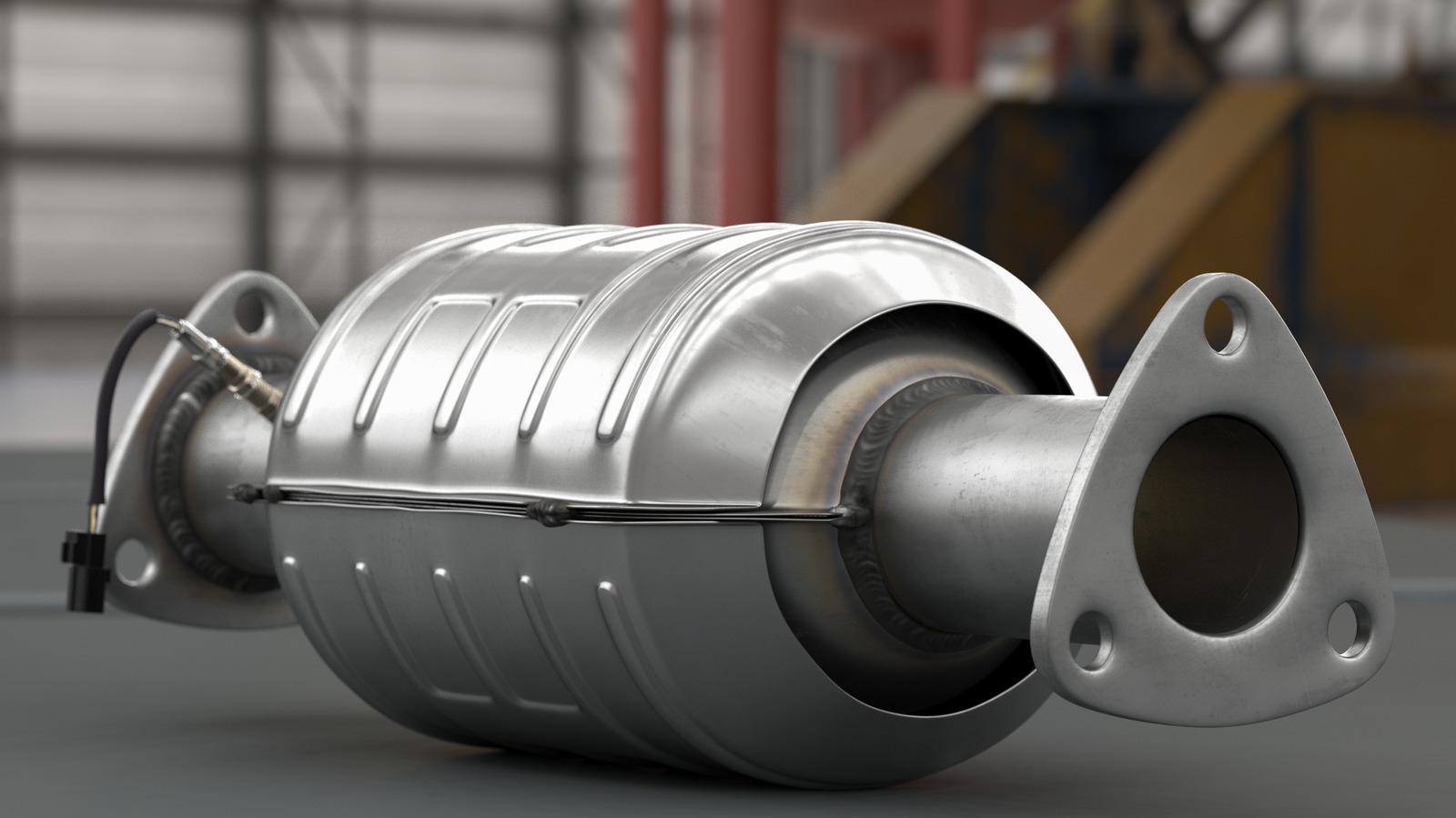

Image: When Did Cars Start Using Catalytic Converters? A Complete History & Impact – Performance Comparison and Specifications

It feels like just yesterday that we were cruising in cars that coughed up black smoke, only to see a sleek catalytic converter under the hood today. The journey from smoky exhausts to clean‑air compliance is a story of legislation, technology, and a bit of automotive drama. In this post we’ll travel back to the moment governments forced a change, explore how converters evolved, and answer the burning question: when did cars start using catalytic converters?

Why Catalytic Converters Became a Must

The automobile had been going strong for decades when increased recognition of the dangers of emissions brought the government to mandate catalytic converters. By the early 1970s, research showed that carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, and nitrogen oxides were major contributors to smog and health problems. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) stepped in, and the Clean Air Act of 1970 set the stage for a technical revolution.

1970s: The First Wave

In 1975, the EPA required all new gasoline‑powered cars sold in the United States to be equipped with a catalytic converter. Early units were two‑way converters—designed primarily to reduce carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrocarbons (HC). They worked, but nitrogen oxides (NOx) remained a problem.

Late 1970s – Early 1980s: The Three‑Way Converter

By 1979, a breakthrough arrived: the three‑way catalytic converter. This design could simultaneously tackle CO, HC, and NOx, turning harmful gases into harmless water vapor, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen. The first production cars with three‑way converters rolled off the lines in 1981, including the 1979 Chevrolet Malibu and the 1982 Ford Escort. These models were early adopters of what would become standard equipment worldwide.

How Catalytic Converters Work

At its core, a catalytic converter is a honeycomb‑like ceramic substrate coated with precious metals—platinum, palladium, and rhodium. When exhaust gases flow through, a series of chemical reactions convert pollutants into harmless compounds. The process can be summed up in three steps:

- Oxidation: CO + ½ O₂ → CO₂

- Reduction: NOx → N₂ + O₂

- Hydrocarbon Oxidation: HC + O₂ → CO₂ + H₂O

Modern converters also feature oxygen sensors and sophisticated engine control units (ECUs) that keep the mixture at the optimal stoichiometric ratio—often 14.7:1 for gasoline engines. This is why you’ll see the term “lambda sensor” pop up in service manuals.

Design & Dimensions of a Typical Converter

| Parameter | Typical Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 12–18 inches (30–45 cm) | Varies by vehicle class |

| Diameter | 3–6 inches (7.5–15 cm) | Fits under most exhaust manifolds |

| Weight | 5–12 lbs (2.3–5.4 kg) | Heavier units use more ceramic |

| Precious Metal Content | ≈5–10 grams total | Platinum, palladium, rhodium mix |

Feature Comparison: Two‑Way vs. Three‑Way Converters

| Feature | Two‑Way | Three‑Way |

|---|---|---|

| Primary pollutants reduced | CO & HC | CO, HC & NOx |

| Typical era | Early‑1970s | Late‑1970s onward |

| Complexity | Simple | Requires precise O₂ feedback |

| Fuel efficiency impact | Minor | Neutral to positive (via ECU tuning) |

Engine Specifications of Early Converter‑Equipped Models

| Model | Engine Type | Displacement | Power (hp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 Chevrolet Malibu | Inline‑4 | 2.3 L | 115 |

| 1982 Ford Escort | Inline‑4 | 1.6 L | 78 |

| 1983 Honda Civic (CVCC) | Inline‑4 | 1.5 L | 76 |

| 1985 Toyota Corolla | Inline‑4 | 1.8 L | 95 |

Price Comparison: OEM vs. After‑Market Converters

| Part Type | Average Price (USD) | Typical Lifespan |

|---|---|---|

| OEM (original equipment) | $1,200–$1,800 | 10+ years |

| After‑market (mid‑range) | $400–$700 | 5–8 years |

| Performance (high‑flow) | $900–$1,400 | 7–10 years |

| Used/Refurbished | $150–$300 | Varies |

Impact on Modern Vehicles

Fast‑forward to today, and catalytic converters are as ubiquitous as airbags and anti‑lock brakes. Even the newest turbo‑petrol engines—think of the 2022 BMW 330i or the 2023 Audi A4—rely on advanced three‑way converters paired with direct injection and sophisticated ADAS (Advanced Driver‑Assistance Systems) that constantly monitor exhaust composition.

Hybrid models, such as the Toyota Prius, often use a smaller converter because the electric motor reduces overall emissions. Meanwhile, diesel engines employ diesel oxidation catalysts and selective catalytic reduction (SCR) systems to meet stricter Euro 6 standards.

Common Myths About Catalytic Converters

- Myth: Converters are a “performance killer.” Reality: Modern designs are tuned to minimize back‑pressure, and many performance cars actually gain horsepower after a high‑flow upgrade.

- Myth: You can run a car without one if you have a “clean” engine. Reality: It’s illegal in most countries and will trigger the check‑engine light almost instantly.

- Myth: All converters are the same price. Reality: Prices vary dramatically based on metal content, vehicle size, and brand.

Future Trends: From Catalytic Converters to Zero‑Emission

As governments push for zero‑emission vehicles, the role of the catalytic converter will evolve. Electric cars don’t need them, but plug‑in hybrids and mild‑hybrids still benefit. Researchers are also experimenting with ceramic‑based converters that use less precious metal, reducing cost and environmental impact.

Conclusion

So, when did cars start using catalytic converters? The answer is a two‑step timeline: two‑way units appeared in 1975, and the three‑way converters that dominate today hit the market in 1979‑1981. Since that pivotal moment, the humble honeycomb has saved countless lives by cleaning the air we breathe, all while quietly humming under the car’s exhaust.

Whether you drive a classic 1978 Ford Mustang or a brand‑new turbo‑charged 2024 Mercedes‑C, the catalytic converter is a silent partner in every journey. Understanding its history not only satisfies curiosity—it underscores why modern emissions standards matter and how technology continues to protect our planet.

Frequently Asked Questions

- 1. What is the main purpose of a catalytic converter?

- To convert harmful exhaust gases—CO, HC, and NOx—into harmless substances like CO₂, H₂O, and N₂.

- 2. When were catalytic converters first mandatory in the U.S.?

- They became mandatory for all new gasoline cars starting in the 1975 model year.

- 3. How does a three‑way converter differ from a two‑way?

- A three‑way converter also reduces nitrogen oxides, while a two‑way only handles carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons.

- 4. Can I replace a faulty converter with an aftermarket part?

- Yes, but it must meet the same emissions standards (e.g., CARB certification) to stay legal.

- 5. Why do some converters have a “heat shield”?

- To protect surrounding components and maintain optimal operating temperature for the catalyst.

- 6. Do electric vehicles need catalytic converters?

- No, because they produce zero tailpipe emissions.

- 7. How often should a catalytic converter be inspected?

- Typically during routine emissions testing or if the check‑engine light illuminates.

- 8. What causes a converter to fail?

\